To effectively elucidate the causal relationships between various economic processes, it is vital to delineate the evolution of their patterns. For example, recent developments in interest rates highlight the potential correlations among different rates. The onset of global trade tensions, initiated by former President Trump’s policies, has prompted notable adjustments, including reductions in rates by various countries due to decisions made by international institutions such as the European Central Bank (ECB) (see https://www.lesechos.fr/finance-marches/marches-financiers/la-bce-choisit-de-baisser-ses-taux-face-a-lincertitude-economique-2160609). Additionally, the Federal Reserve (FED) is facing pressure to lower its rates in response to these external influences (https://www.marketwatch.com/story/trump-is-furious-that-fed-wont-cut-interest-rates-like-ecb-heres-why-powell-wont-budge-162dfdaa).

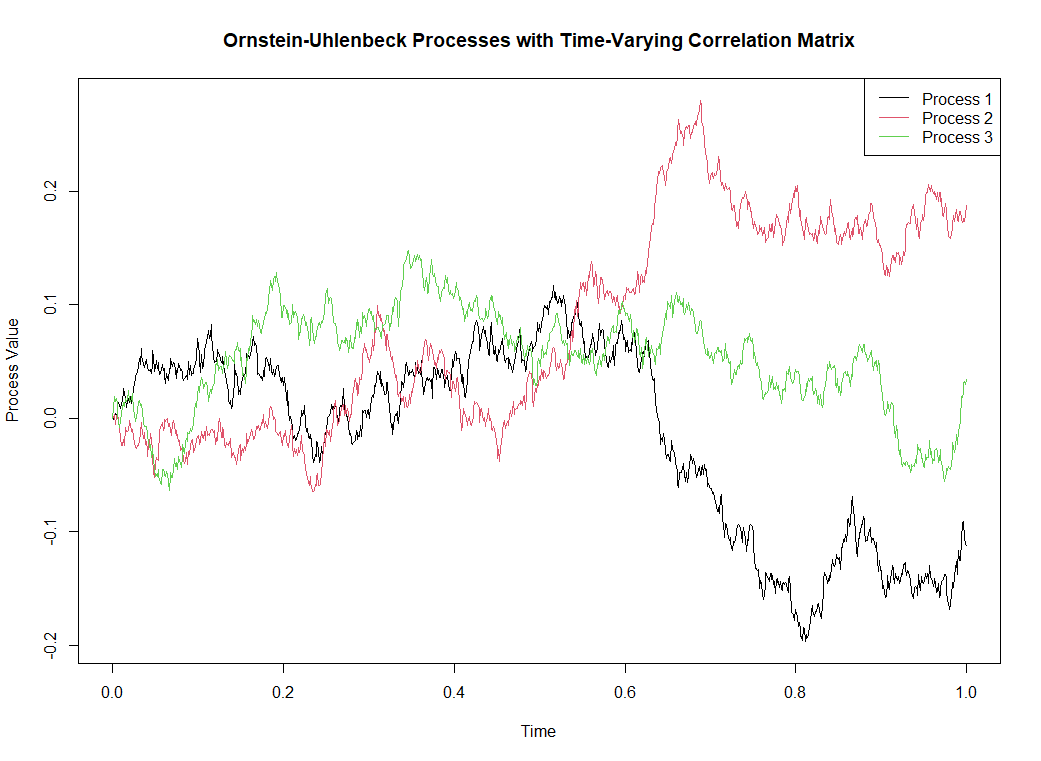

A straightforward approach to modeling the evolution of interest rates is through stochastic processes, such as the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process. Although potential negative rates present a challenge, our focus will be on further exploring multivariate scenarios. Should it be imperative to avoid negative rates, the Heston-White model presents a viable alternative. For a thorough examination of interest rate modeling, refer to the comprehensive work of Damiano Brigo and Fabio Mercurio.

In the following, we are interested in the stochastic differential equation of the form

where the second term shall be generalized. But what generalization?

We thus introduce the vector stochastic process  of dimension

of dimension  (

( interest rates),

interest rates),  is a

is a  matrix describing the trends of the vector stochastic processes.

matrix describing the trends of the vector stochastic processes.

In other posts of the present blog, the following equation was proposed.

where  is a function, assumed to be at least continuous on

is a function, assumed to be at least continuous on  (or

(or  -Borelian, or "Borealian" to be more precise). In addition,

-Borelian, or "Borealian" to be more precise). In addition,  is assumed to be some positive number. Finally,

is assumed to be some positive number. Finally,  is a vector of standard Wiener processes. The function

is a vector of standard Wiener processes. The function  is giving non-linearities and further depenencies

is giving non-linearities and further depenencies

First, we note that this equation gives

This means that  is a sum of linear forms (i.e. "

is a sum of linear forms (i.e. " ") defining some metric of integration. Since

") defining some metric of integration. Since  and

and  are the only forms which we consider in this equation, then we heuristically we:

are the only forms which we consider in this equation, then we heuristically we:

where the  's are Borealian functions of

's are Borealian functions of  and

and  and we ignore the terms of the form

and we ignore the terms of the form  with

with  , and

, and  with

with  . Considering now the fact that

. Considering now the fact that  is only depending on

is only depending on  , this means that the term of the form

, this means that the term of the form  could be set to zero. Thus we have:

could be set to zero. Thus we have:

Using again the fact that  only depends on

only depends on  , we should have

, we should have

where the  's are other Borelian functions but only depending on

's are other Borelian functions but only depending on  (and

(and  ). Repporting to Eq. (1), we then have:

). Repporting to Eq. (1), we then have:

This (vector) equation turns out to be the most possible general stochastic differential equation related to the function  introduced in Eq. (1). Note here that

introduced in Eq. (1). Note here that  is a vector of dimension

is a vector of dimension  and

and  is a matrix of dimension

is a matrix of dimension  , representing the covariance matrix associated with the vector

, representing the covariance matrix associated with the vector  . In fact, this equation is an Itô process.

. In fact, this equation is an Itô process.

If the processes only have dependencies in their stochastic terms, we shall set  to be a vector only depending on time

to be a vector only depending on time  , i.e.

, i.e.  , so that the final quation of interest is given by:

, so that the final quation of interest is given by:

We integrate this equation by setting:

The Itô's lemma gives:

Therefore, integration of this process finally leads to:

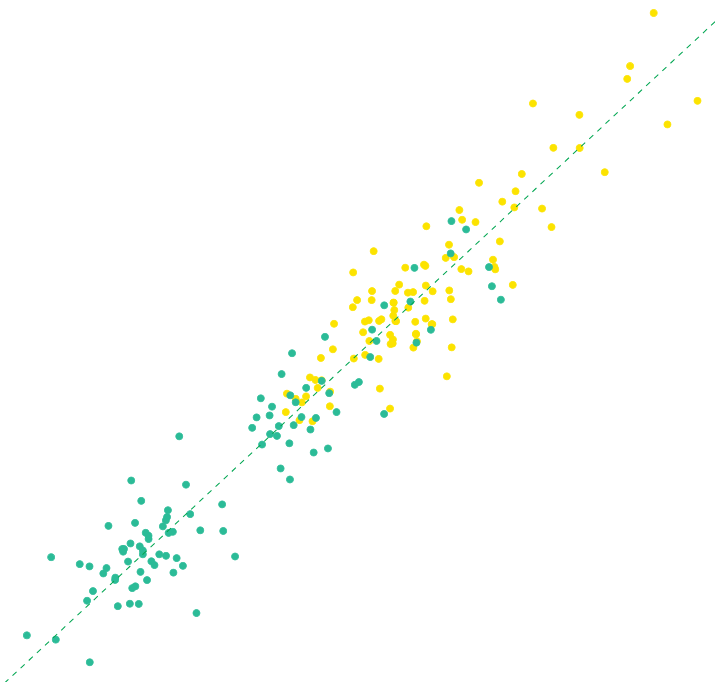

Now, we note that the only random term is the third one, which has zero expected value. Therefore, we have

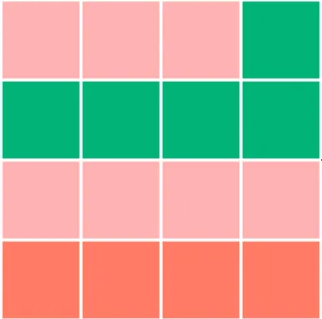

In words,  is following a normal vector process with covariance

is following a normal vector process with covariance  . It shall be interesting to see in which circumstances the matrix

. It shall be interesting to see in which circumstances the matrix  and vector

and vector  may lead to a non-explosive process.

may lead to a non-explosive process.

can be derived as follows:

is a little more nuanced and will require more wrangling. Recall the definition of covariace between two non-overlapping processes:

and that using the Quadratic Covariation we can show:

in (49) can be expressed as:

and

our expression in (47) simplifies to:

and

is the correlation term

. Therefore, the expectation of the diffusion integral in (29) is given by: